How Fast Should Your Long Runs Be?

“Good things come slow, especially in distance running.” Bill Dellinger

With these words, retired middle-distance Olympian, Bill Dellinger, most likely referred to the fact that there are no shortcuts to fitness, strength or stamina in running. His words are, however, equally suited to long runs. A staple in any serious runner’s artillery, long runs train the body to better utilize oxygen, preserve glycogen stores by utilizing fat as fuel, and altogether become more efficient. And there certainly also are no shortcuts to that.

But while most experienced runners grasp the importance of a weekly long run, many feel uncertain about how fast this run should be. Can you miss out on the benefits of a long run if it’s done too slow? And will running too fast negatively impact on the rest of your training? Here are some thoughts on the matter from two respected and well-known leaders in the industry.

What is the purpose of your long run?

First of all, let’s just clarify what we mean by the term “long run”. While some long runs are aimed at simulating marathon conditions and teaching you to finish fast and strong, others are designed to simply build aerobic endurance by putting “time on your feet”. And while both of these types of long runs serve an important purpose at various stages of your training and racing cycle, we’ll be looking at the latter in this blog post.

What physiological adaptations contribute to building aerobic endurance?

According to running coach and 2:22 marathoner, Jeff Gaudette, it’s important to look at the physiological benefits that you want to reap from your “easy” long runs before rushing into them. Research has shown that each of these physiological adaptations, in turn, optimally take place at specific running paces, something you should keep in mind when executing your long runs in order to obtain the best possible results.

So what exactly are these physiological adaptations and at which paces are they optimized? Gaudette lists the following:

- More capillaries. Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the body, delivering both nutrients and oxygen to working muscles. More capillaries, therefore, equals more oxygen and more nutrients distributed to working muscles. And that’s something you definitely want if you’re aiming to run more efficiently. So how can you optimize capillary development? According to Gaudette “capillary development appears to peak at between 60 and 75 percent of 5K pace”.

- More myoglobin. Oxygen molecules that enter muscle fibers through the bloodstream bind to special proteins called myoglobin. In instances where oxygen then becomes limited, such as during a race, the myoglobin releases its oxygen to the mitochondria to enable it to fulfill its job. In other words, the more myoglobin you have in your muscles, the more oxygen can be delivered to it while running. And under which conditions do maximum stimulation of Type I (or slow-twitch) muscle fibers occur? Running at approximately “55-75 percent of 5K race pace,” says Gaudette.

- Better glycogen storage. For races lasting longer than 90 minutes, the more glycogen you can store in your muscles, the longer you can prevent hitting the wall. Which is exactly what easy long runs teach your body. Running out of stored glycogen on the run acts as a stimulus to teach the body to store more next time. And while no research-backed optimal paces have been published in this regard, Gaudette says that, from personal experience and experience in training elite runners, “a pace of about 65-75 percent of 5K pace is optimal”.

- More mitochondria. Mitochondria are microscopic organelle that play a vital role in the production of energy in muscle cells. In short, the greater the density of mitochondria in your muscle cells, the more energy you can generate during running, allowing you to keep going harder and faster for longer. And at what pace is the development of mitochondria optimized? According to research done in the early 80s, running for 90 minutes at between 70 and 75% of one’s VO2max. Which, according to Gaudette, translates to 65 to 75% of 5K race pace.

So what does all of this mean? Where’s the sweet spot or overall optimal easy long run pace where all of these physiological adaptations can be triggered in one go? According to Gaudette, it’s “between 55 and 75 percent of your 5K pace, with the average pace being about 65 percent”. Which, we’re sure you’ll agree, translates to a pretty easy pace.

Going faster doesn’t necessarily equal better physiological adaptation

Interestingly, Gaudette mentions that running faster than 75% of your 5K race pace during your easy long runs will not result in any significant additional physiological benefits. Meaning that doing these runs too fast could actually hinder your overall training by wearing you out and hampering recovery, all without any meaningful benefit. So resist the urge to go harder while running long and rest assured that you’re going at just the right pace to allow your body to do what is needed to get better.

Other opinions

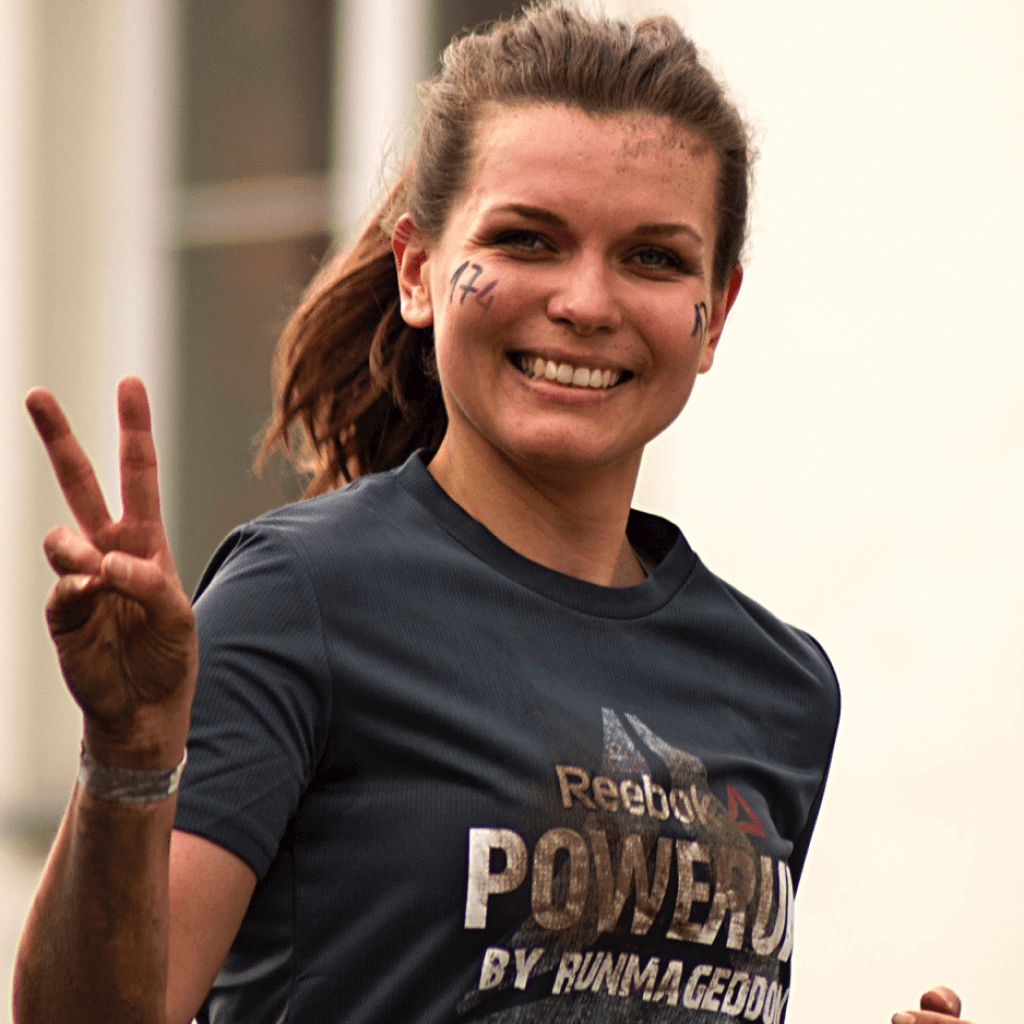

But what do other experts say? Do they agree with Gaudette? While best-selling author and “coach of this generation”, Jenny Hadfield, agrees that easy long runs should be purpose-focused (i.e. what are the adaptations that you want from these runs?), she feels that it should be done according to effort, not pace. “There is a calculation that suggests you should run two minutes per mile slower than your predicted marathon pace. Heck, I used to say that when I first started coaching, until I realized it doesn’t work and leaves us mortals thinking ‘Well how do I know my marathon pace?’,” she quips.

So what are Hadfield’s recommendations regarding the ideal easy long run pace? “Run in the Yellow (happy) Zone and at a slow, easy conversational effort. You know you are there when you can hold a conversation and recite a few sentences out loud without effort, and when you can’t hear your breathing“, she suggests. “Your goal is to simply go out and run easy for a long time”.

The takeaway

So whether you prefer sticking to a pre-determined pace, or simply running according to effort, be sure not to push too hard on your easy long run days. Stick to the pace or effort level suggested, and you’ll soon feel your body adapt and get better at doing what you love.

Sources

- , How to calculate your long run pace, Online publication

- , What is the optimal long run pace?, Online publication

- , Are you sabotaging your long run by running the wrong pace?, Online publication

- , How fast should your easy long runs be?, Online publication

Latest Articles

Is Running on a Treadmill Easier Than Running Outside?Runners have their own preferences, whether it is treadmill running, running outside on the road, or exploring trails. So...

Is Running on a Treadmill Easier Than Running Outside?Runners have their own preferences, whether it is treadmill running, running outside on the road, or exploring trails. So... Is It OK to Use Trail Running Shoes on the Road?While trail running shoes can be used on roads, especially in situations where a runner encounters mixed terrains or pref...

Is It OK to Use Trail Running Shoes on the Road?While trail running shoes can be used on roads, especially in situations where a runner encounters mixed terrains or pref... How to Fix Sore Quads After Running?Rest, ice, gentle stretching, and over-the-counter pain relievers can help soothe sore quads after running. Also, ensure ...

How to Fix Sore Quads After Running?Rest, ice, gentle stretching, and over-the-counter pain relievers can help soothe sore quads after running. Also, ensure ... 10 Fruits With The Most Electrolytes to Replace Sports DrinksThese fruits are high in electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, essential for hydration, muscle function...

10 Fruits With The Most Electrolytes to Replace Sports DrinksThese fruits are high in electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, essential for hydration, muscle function...