The Amateur’s Guide to Running at High Altitude

Elites have been doing it for ages. And it certainly gives the Kenyans an edge. So what exactly is it about high altitude running that makes it so popular with the pros? And, perhaps more importantly, will running at altitude instantly transform a back-of-the-pack amateur into a star?

Here’s an amateur’s guide to running at altitude.

How High is “High”?

So how high exactly is “high altitude”? Ben Hahn, formerly involved with offering custom high altitude training programs as part of the Mancos Project in Colorado, considers anything higher than 1 400 m (+-4 590 ft) above sea level to be high altitude. He adds, however, that he believes that training between 2 000 m and 2 400 m (+-6 560 to 7 870 ft) above sea level is ideal.

The Perks of Training at a High Altitude

But why does Hahn feel that training at such a high altitude is ideal? As a result of differences in atmospheric pressure, air is more dense at lower altitudes. Which means that oxygen is more readily available for uptake at sea level than it is at high altitude. And while training at sea level therefore sounds ideal, the opposite is actually true. Because while running at sea level is perceived to be “easier” than running at altitude, the latter forces the body to make some pretty nifty adaptations. Like, for instance, the following:

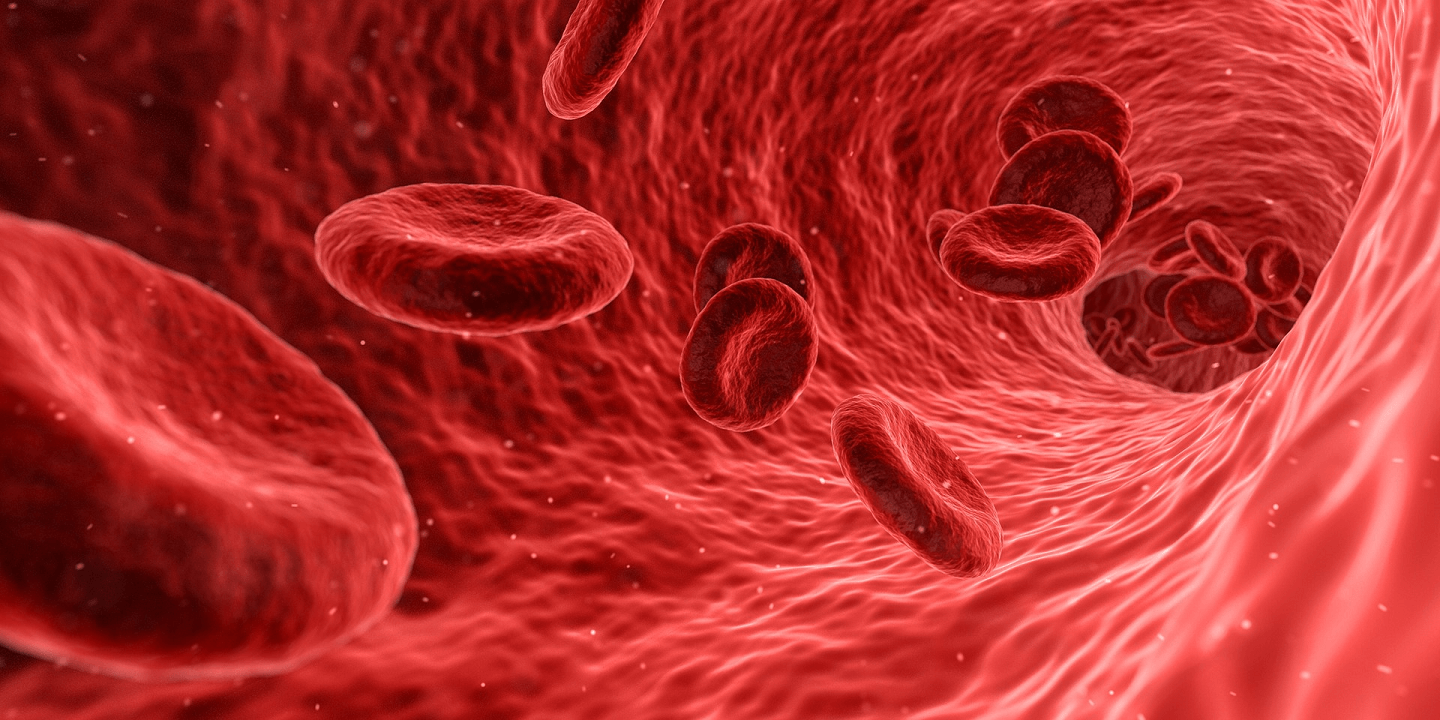

- Running at high altitudes forces the body to produce more red blood cells. Through the production of erythropoietin or EPO, the body is stimulated into producing more red blood cells. A higher red blood cell count, in turn, leads to improved oxygen uptake in the body – a quality that can come in very handy when racing at sea level.

And while this perk of running at high altitude takes time to develop and manifest, others are immediate. According to running coach, Jack Daniels, the endurance-hindering lack of oxygen at higher altitudes is somewhat counteracted by a decrease in air resistance. Which means that, over shorter, faster races, a decrease in air resistance may help you clock faster times. This phenomenon is especially relevant to sprinting distances and, as a result, sprinting times clocked at altitude are not allowed for record-keeping purposes.

Tips for Training and Racing at High Altitude

Not everyone is lucky enough to live and train at altitude, though. So, for those of us who train at lower altitudes and wish to travel to and participate in high-altitude races, the following is important to keep in mind:

Pre-race

- Arrive early. Acclimatizing to high-altitude conditions takes time. In fact, according to Hahn, full adaptation can take months. But don’t let that discourage you! Hahn is quick to add that most athletes tend to start feeling “normal” after approximately a 10-day acclimatization period. So be sure to make your travel arrangements accordingly!

- Or arrive as late as possible. Alternatively, if spending a week or more at your race destination before the race is out of the question, running coach and -legend, Hal Higdon, recommends arriving as close to race day as possible. Oxyhaemoglobin levels are lowest approximately 72 hours after arriving at high altitude, so carefully time your arrival to fall within 72 (and preferably within 48) hours of your race.

- Adapt your expectations. Whether you arrive at altitude ten days or 24 hours before your race, you will by no means be fully acclimatized when the starting gun fires. So do yourself a favor and adjust your expectations. Instead of aiming for a good finishing time, focus on taking in the scenery and relishing the experience instead.

- Adapt your program. It’s a good idea to ease into your acclimatization runs once you’ve arrived at altitude. Start off with an easy 20-minute run on the first day, and limit your runs to every other day for your first week. And, perhaps most importantly, listen to your body and adapt your program accordingly.

- Do a short, easy shake-out run as soon as possible after arriving. Running coach and professional runner, Megan Lizotte, believes in the value of an initial shakeout run. It “allows you to get a taste of what you’re in for and re-energizes you from the travel”, she says.

During your race

- Start your race slowly. While not starting out too fast is always a good idea in any race, it’s vital when racing at altitude. Remember that breathing while running might feel harder at altitude. So give yourself a chance to settle down and find your rhythm before (slightly) stepping things up.

- Make use of breathing techniques. Lizotte recommends relaxing your jaw and breathing out with a “ssss”- or “th”-sound while running. She believes that this technique “takes the focus off of the pain and sense of panic that runners can feel”.

- Don’t force your normal running pace. And even after you’ve started out slowly and found your rhythm, you’ll probably have to run at a slower pace than normal. Take it easy when you need to. Walking up a hill is nothing to be ashamed of at altitude.

- Remember to drink according to thirst. It may feel like you’re sweating less at high altitude, so pay extra attention to your thirst levels and hydrate accordingly.

Post-race

- Pay extra attention to recovery post-race. Your body may need a little extra TLC after running at altitude, so be sure to get enough good quality sleep, and focus on proper post-race nutrition.

Acute Mountain Sickness: Are You at Risk?

And what about the cons of running at high altitude? Surely it must have some risks as well? An article published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports in 2008 concluded that transient acute mountain sickness (AMS), or altitude sickness, which is usually characterized by headaches and nausea, is present in 10 to 30% of subjects at altitudes between 2 500 and 3 000 m above sea level. The authors furthermore concluded that pulmonary edema, where fluid starts to accumulate in the tissue and air spaces of the lungs, becomes a risk at heights above 3 000 m above sea level. Cerebral edema, where fluid accumulates in the brain and causes swelling, generally poses a risk at heights above 4 000 m above sea level.

And while any sea-level athlete can fall victim to AMS, a number of factors can increase your likelihood of being affected. This includes:

- Your genetic make-up.

- The rate at which you ascended to a higher altitude.

- Whether or not you had a respiratory infection while changing altitudes.

But is AMS preventable? While not 100% foolproof, the training and racing tips listed above should help you combat its effects.

Stop and Smell the Roses

So while running or racing at altitude may seem like the ultimate adventure, it’s good to note that it does come with some risk. So prepare as best you can, ease into it, and remember to stop and smell the roses. It is, after all, not everyday that you get a chance to run on top of the world!

Sources

- , How to Adjust Your Running for a Race at High Altitude, Online publication

- , 5 Tips to Beat High Altitude Sickness, Online publication

- , What you need to know about running at altitude, Online publication

- , Altitude training for the non-elite, Online publication

- , Training for a high altitude marathon, Online publication

- , General introduction to altitude adaptation and mountain sickness, Scientific journal

Latest Articles

Is Running on a Treadmill Easier Than Running Outside?Runners have their own preferences, whether it is treadmill running, running outside on the road, or exploring trails. So...

Is Running on a Treadmill Easier Than Running Outside?Runners have their own preferences, whether it is treadmill running, running outside on the road, or exploring trails. So... Is It OK to Use Trail Running Shoes on the Road?While trail running shoes can be used on roads, especially in situations where a runner encounters mixed terrains or pref...

Is It OK to Use Trail Running Shoes on the Road?While trail running shoes can be used on roads, especially in situations where a runner encounters mixed terrains or pref... How to Fix Sore Quads After Running?Rest, ice, gentle stretching, and over-the-counter pain relievers can help soothe sore quads after running. Also, ensure ...

How to Fix Sore Quads After Running?Rest, ice, gentle stretching, and over-the-counter pain relievers can help soothe sore quads after running. Also, ensure ... 10 Fruits With The Most Electrolytes to Replace Sports DrinksThese fruits are high in electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, essential for hydration, muscle function...

10 Fruits With The Most Electrolytes to Replace Sports DrinksThese fruits are high in electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, essential for hydration, muscle function...